In the absence of songs, language and an intact dreaming-although he knows his totem or ‘meat’ is the mibun or wedgetail eagle-Twoboy has to prove his Bundjalung identity the whitefella way: suited up, in the tribunal. Unfortunately for Twoboy, his fight is a bit more complicated. In Bundjalung, you might greet another blackfella by asking: 'Jingawahlu?' Literally, ‘Where do you walk?’ but there is a deeper meaning: 'Where are you from, where have you been, where are you going?' Living and walking on your own country confers a sense of belonging. He's a dreadlocked Johnny-come-lately with unproven claims to Bundjalung country at least, there is no one who is prepared to corroborate his story that he and not Bullockhead is the 'one true blackfella for this place.' Twoboy has been living off-country on the outskirts of Brisbane after studying law at the University of Melbourne. Jo is trying to avoid becoming hopelessly entangled in the fight between the charming outsider Twoboy Jackson, whose great-grandfather left his Bundjalung country in 1864 after being kidnapped and forced to join the notorious Native Police, and the recognised native title claimant, the aptly named Oscar Bullockhead. She has made her home on fictional Tin Wagon Road in an entirely fictional valley near Mullumbimby, a haven for self-funded retirees, hippies and burnt-out tree-changers.

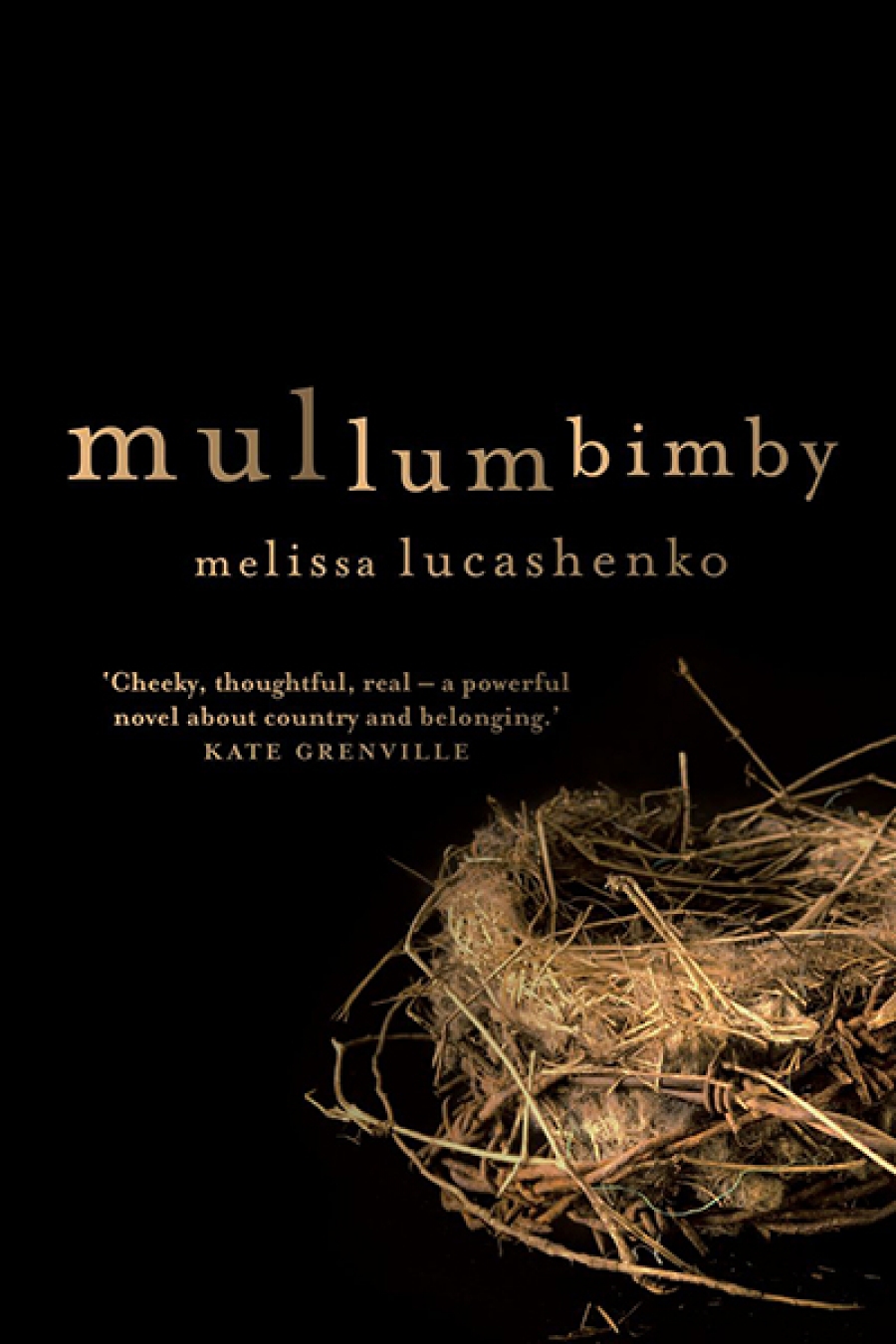

In the novel, Jo Breen has retreated to her ancestral homeland in Bundjalung country where she labours among the dead as caretaker in the Mullumbimby cemetery. She is quick to say that the novel is a work of fiction, despite its real setting in the unimaginably beautiful hinterland on the far north coast of New South Wales. Melissa Lucashenko's latest novel, the long-awaited Mullumbimby, is honest and nuanced in the way it treats the cultural warfare that can ensue in bitter disputes over native title. The politics of belonging can be a tricky business.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)